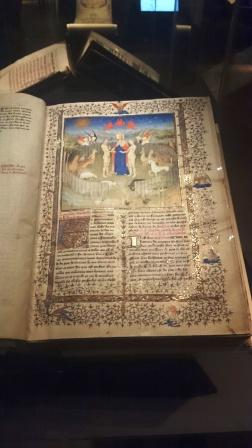

Being an art and history enthusiast, I jumped at the chance to attend the recent press view of the Colour exhibition of illuminated manuscripts at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, which is now open to the public. And what a glorious celebration of art, science, opulence, religion and humanity it proved to be!

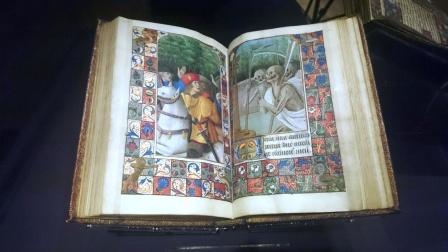

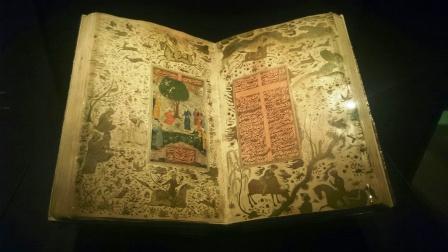

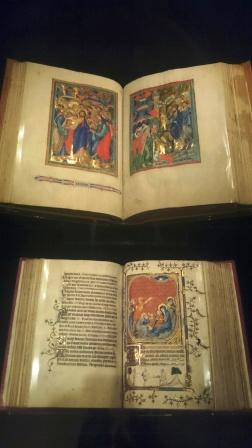

Displayed across two rooms are 150 of the finest and most awe-inspiring examples of complete illuminated texts and fragments from long-lost volumes, produced between the 8th and 17th centuries. The majority of these come from the museum’s own collection, as bequeathed by the institution’s founding father Viscount Fitzwilliam in 1816 under strict instructions that they should never leave the building. Indeed, the exhibition itself marks the museum’s bicentenary.

Arranged as a logical and easy-to-follow journey through the art of illumination, the exhibition also invites us behind the scenes, revealing the results of recent art historical and scientific research into the creation of these mind-boggling artworks.

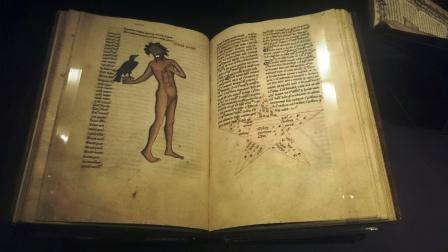

After four years of analysis and discovery, the Fitzwilliam’s curators, scientists and conservators have traced the creative process from the illuminators’ original ideas, through to their choice of pigments and painting techniques, to the completed masterpieces. Using non-invasive scientific processes such as X-rays, the team was able to avoid causing any damage through taking samples.

Infra-red imaging and mathematical modelling were even able to reconstruct the original composition beneath modern paint layers in a ‘censored’ Garden of Eden!

Thanks to this cutting-edge research, we are introduced to the specific materials that were used to create the pigments – from plant materials and lichens to minerals such as azurite and lapis lazuli, and even ground glass – plus, of course, the dazzling gold that reflects the value and importance of these manuscripts.

A range of pigments was used not only to create a colourful composition, but to enable the artist to convey a sense of depth and communicate symbolic meaning. For example, a pallid palette applied to a human figure indicated an imbalance in the ‘four humours’, and separated the living from the dead.

I was fascinated to discover the close relationship between alchemy and artistic practice; gold, for example, was known as ‘the sun’ and silver as ‘the moon’. The exhibition’s alchemical scroll, partially rolled out in a glass case and viewable in its entirety on the museum’s digital resource, was undoubtedly one of the stars of the show.

It turns out, therefore, that not all illuminated manuscripts were religious texts created by monks, as is widely believed. “From the 11th century onwards professional scribes and artists were increasingly involved in a thriving book trade, producing religious and secular texts,” explained research scientist Dr Paola Ricciardi.

Many were commissioned by wealthy patrons such as cardinals and members of the nobility. Just a small section of the illuminations for one of the exhibits is documented to have cost £30,000!

Do visit the exhibition if you can – it’s a rare chance to see these priceless artefacts first hand, and to immerse yourself in the stories behind their creation. You may find that you carry that sense of a connection with the past with you as you leave the museum – I certainly did!

Colour: The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts

30 July-30 December 2016, entry free

Fitzwilliam Museum, Trumpington Street, Cambridge